How much cash vs. debt should you use in your next Micro-SaaS acquisition?

Balancing debt and free cashflows for strong returns

It's possible to acquire a business for very little out-of-pocket cash, even just a symbolic dollar, but that's not always the right move.

You can finance about 70% out of the gate with a good lender, and can seller-finance as much as 25-30% of the acquisition too.

That allows you to buy something with 0-5% in cash out of your own pocket.

The advantage is you get to leverage your capital for a greater outcome than its size is supposed to yield.

Interested?

Say the business is selling for $100k.

You could buy it with just $5k, with some creative instrumentation.

The disadvantage with leveraging that much is that servicing your two debts above (loan + cash balance) likely sacrifices all of your free cashflows.

As long as you can make the numbers work, you’ll own the business for a very low amount of cash, but it will run at a risky break-even.

There are good and bad candidates for debt and cash.

A business growing month-on-month with a strong idea of what the run rate will be 12, 24 and 36 months later is a great candidate for debt.

Sure, you’ll run at break-even as of closing, but your free cashflows will grow as top-line revenue grows because your debt service are fixed costs.

You could then bank the difference as the business grows.

On the opposite side of micro-acquisitions, which seek stable businesses with predictable income, debt-service is not always the right choice, since you want the highest net income you can get.

You’ll start-off at break-even, but you’ll never depart from that state because revenue isn’t growing.

You could put in the work to actively increase the revenue, but that has to be compatible with your investment thesis.

In general, it’s not compatible with mine since I’m building a portfolio with the intent to use its free cashflows to buy-back my time as a full-time bootstrapper.

It’s buying my way to freedom. My IRR is my free cashflows. I don’t want to be spending time actively working on my portfolio. I have greater aspirations.

If and when I choose to sell my portfolio, it will basically represent taking my initial investment (or more) back, and having perceived excellent revenues during the lifetime of the investment.

Fund II — which is out of scope for now — is likely going to have a more aggressive thesis which will reinvest all of the free cashflows into the businesses.

For now, the function of the MicroAngel fund is to let me play the game full-time. Thus, it’s important to base the decision to use debt, cash or all-cash by factoring a few elements.

First, do you even have enough cash to buy something outright — if you don’t, you’re naturally limited to using at least some debt to buy.

If you’re going to use debt, beyond the obvious impact on your costs, take into account how long it typically takes to secure funds and the level of detail you need to go into with your lender to satisfy their requirements.

Then, multiply all that by a factor of 2x or 3x.

I’ve lost a ton of deals to slow financing.

Another fact is that you’ll be at a natural disadvantage relative to all-cash buyers who move more nimbly, and most importantly, have the option to use all-debt, some debt or no debt to orchestrate their transactions.

Second, you need to work backwards from your cashflow requirements, which likely means your P&L and growth plan.

What is going to happen post-acquisition? Will you need to reinvest part or all of the free cash flow? Are there any fixed costs? How much will be leftover after servicing your debts & costs?

Mix-and-match different scenarios to see how it affects your numbers. Consider scenarios using these financial instruments:

cash

earn-outs

lender financing

seller financing

convertible debt

equity

and so on…

Educate yourself on the different ways you can execute the transaction while bearing in mind that some financial instruments will impact your free cash flows in ways you may not expect.

At the end of the day, what matters is returns. And the scenario you pick is going to have an impact on your cash-on-cash returns.

I really ought to create a proper calculator for this. But the general idea goes like this:

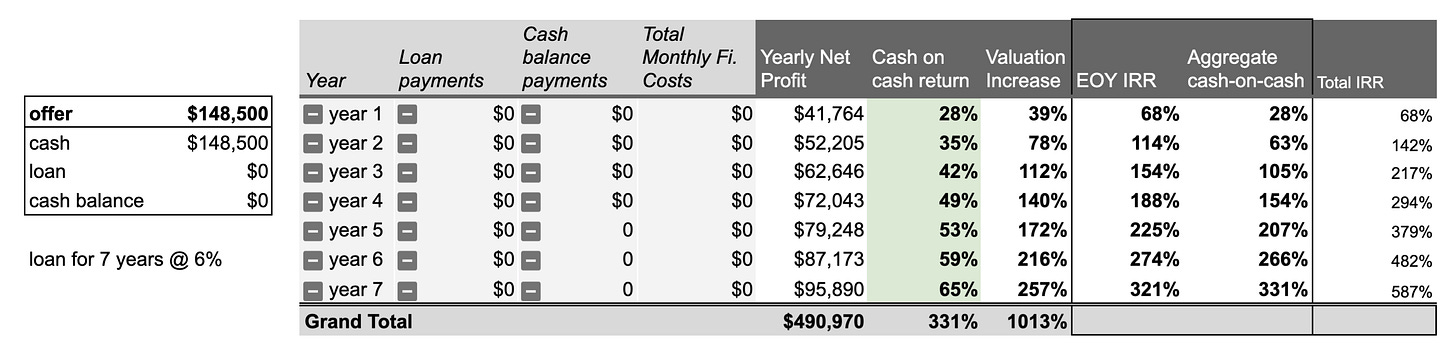

Let’s say I’m buying something for $148,500.

If I go in all-cash, my returns look something like:

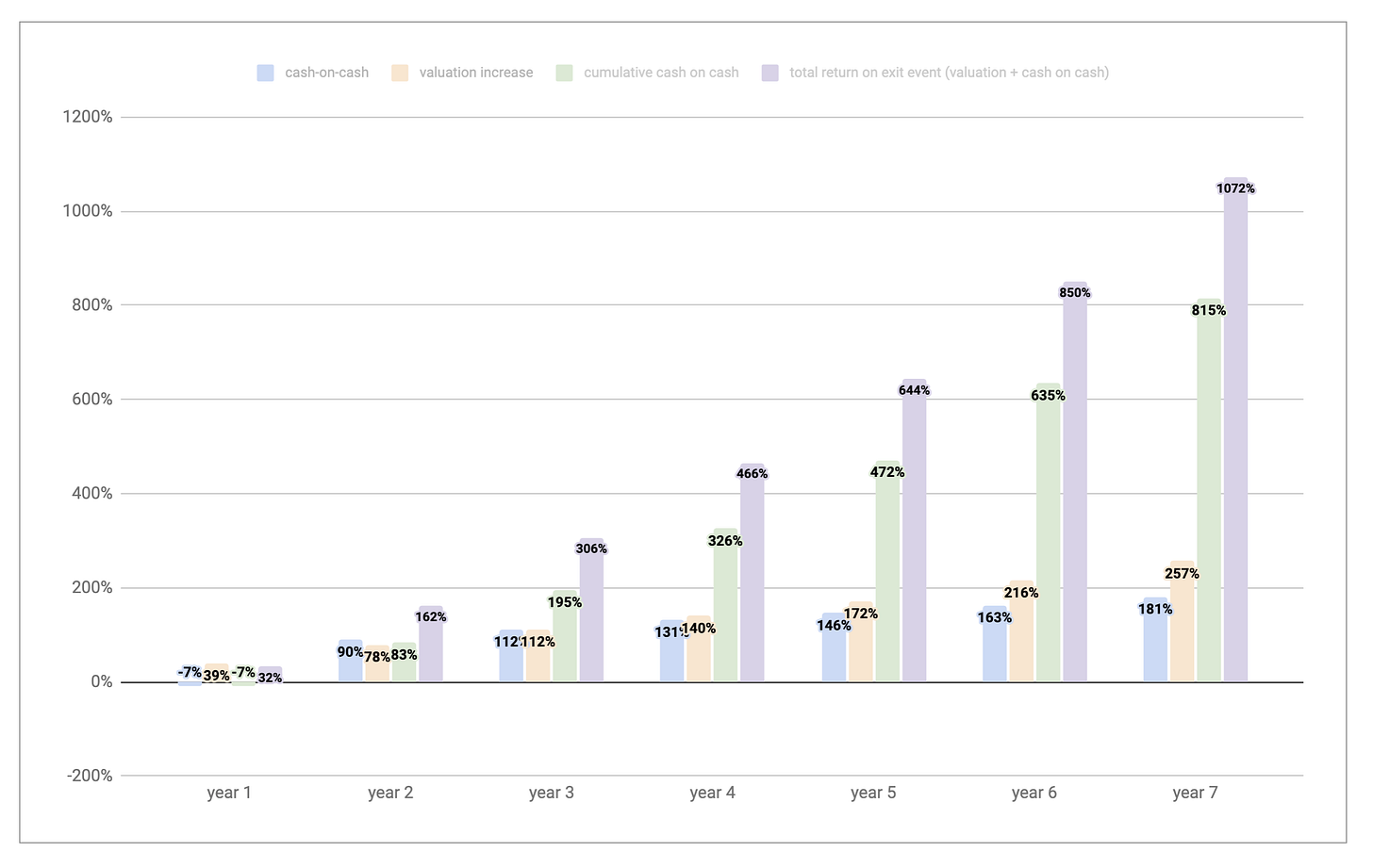

Year 1: 28% cash-on-cash, 68% total return

Year 2: 35% cash-on-cash, 142% total return

Year 3: 42% cash-on-cash, 217% total return

Cash-on-cash is how much lands in your pocket compared to your investment, each year. If I clear $41.7k on a $148.5k investment, that defines a cash-on-cash return of (41.7/148.5) 28% per year. If revenues were to stay constant, that also means a payback period of (100/28) 3.57 years. Thankfully, revenues are growing, so the payback period steadily decreases over time.

Valuation increase is the result of ARR growing over the year.

Cumulative cash-on-cash is the cumulative income I’d have collected from the investment, which matters to me in Fund 1

Total return on exit event is what my total return would be like if I ended up selling the product at the end of that year. It’s the sum of the total valuation increase plus the cumulative cash-on-cash returns.

My cash-on-cash return is growing every year because the product’s top-line revenue is growing, whether I show up or not.

What’s interesting about this dynamic is that not only am I securing strong returns on a cash-on-cash basis, but if I consider how much the product’s value grows as a result of its ARR growing, then my true return is much higher (67%-68% year 1):

EOY1 cash-on-cash return: 28%

EOY1 valuation increase: 39%

EOY1 total return: ~68%

This allows me to take advantage of the arbitrage between the price I pay today and the price I’ll sell for in 2-3 years.

Since platforms like MicroAquire make it so easy to sell, that makes this return really liquid to boot. I can get out anytime.

That’s an additional bonus on top of the cash-on-cash returns I’ll be collecting along the way, which is why my entire investment thesis is all about cash flow for Fund 1.

I focus only on simple-to-operate products I could feasibly buy-and-hold, if I so ever choose, and rely only on the cash-on-cash returns1. Anything extra I get when I sell is considered gravy.

Importantly, you may not be inclined to field $150k in a single transaction. That’s a matter of style and budget.

How much do you expect to spend on your next acquisition?

Let’s say you only have $100k in cash to spend.

You could organize the transaction a bunch of different ways, and each scenario will yield a different return and payback period:

Scenario A — $100k cash + $48.5k balance (12 month term)

In this scenario, you’re trying to finance a whole third of the transaction from the seller themselves through a promissory note2.

The idea is simply to pay the cash balance over some term, typically 12 months and not longer than 24 months since most sellers prefer all-cash transactions.

You should know: the larger the amount you finance, the less likely the seller is to take the deal.

Everyone wants to ride off into the sunset. Get a clear grasp of what that number would be like, and then finance the rest as much as you can.

If you go through with this scenario on a 12-month term, your cash-on-cash returns would look something like this:

Year 1: 5% cash-on-cash, 44% total return

Year 2: 52% cash-on-cash, 136% total return

Year 3: 63% cash-on-cash, 232% total return

The first year returns take a nose-dive and you’re pretty much running at break-even due to servicing the cash balance.

Despite this, the company’s valuation would still be expected to climb by nearly 40% over the course of the first year — and that’s a return you wouldn’t have had to pay out-of-pocket to perceive.

Of course, the big benefit here is your returns explode as of year two. A 52% cash-on-cash return is magician-level stuff in my books.

It’s not a bad deal at all — you reduce your out-of-pocket cost by 33% but it forces you to defer cashflows from the product for a whole year.

If you’ve got strong enough personal income, this is an entirely viable strategy, especially to pursue 50%+ cash-on-cash returns.

It’s fine if you’re looking to park $100k today to unlock $50k/yr in 12 months. It’s longer-term thinking that is typically enabled by self-sustenance.

If you don’t have a need to pull out cash flow, then you won’t mind running at break-even for a year.

One of the biggest advantages to seller financing is that it’s like being instantly approved for a loan.

On the seller’s side, they don’t have to wait for you to get approved, which also saves them a lot of headache on the documentation side.

Transacting quickly is more than just a competitive advantage as a microangel. I’d say it’s a growing requirement.

As micro-entrepreneurship grows, so to does the number of micro-angels with deep enough pockets to price you out of deals with all-cash offers. Or worse, they could be transacting quickly enough that you become irrelevant as you try securing financing.

Something else to consider is whether you’re able to secure seller financing terms without paying interest.

That might sound crazy, but the typical Micro-SaaS seller does not mind a reasonable cash-balance, and doesn’t even broach the subject of interest for the financing of it.

Think about it — if a seller is open to offers, then they’re open to terms, too:

If they do have a set price, you can pay it but set the terms (‘I’ll pay your price on my terms’) so it’s still worth it

If they don’t have a set price, then you have free reign to structure your initial LOI however you like, including terms

This can work out both ways for you — it’s an additional tool you can use to sweeten the deal (“I’ll throw in a 5% interest on the cash balance”) or it can be something that becomes a requirement if another buyer comes through with an interest-based cash balance offer.

Don’t be dishonest about it.

I’ve learned that educating the seller is far more in my interest than that of other buyers for the simple reason that sharing information like this earns credibility and trust with the buyer.

Scenario B — $100k cash + $48.5k loan (7 year term)

Here, the main difference is you’re applying the loan over a much longer period of time. It also means you’re paying way more interest, which eats into your overall returns.

That said, it still allows you to buy the company with less out-of-pocket, and your cash-on-cash returns out of the gate are going to be healthier because your debt service every month is less of a burden.

Eventually, the loan might become an afterthought provided the revenues grow at a healthy pace.

In this scenario, the cash-on-cash returns are healthy because the debt service is not a big burden:

Year 1: 34% cash-on-cash, 74% total return

Year 2: 45% cash-on-cash, 158% total return

Year 3: 56% cash-on-cash, 247% total return

When you consider the valuation increase as well, your return every year becomes stronger despite the debt service — in this case it is totally inconsequential to your return:

Your total return is a little higher because you didn’t spend $150k out of pocket, and spread out the loan over a long enough term to make up for the difference.3

In this case, getting a $50k loan over 7 years at a small interest rate is an excellent choice to maximize the total return while maintaining healthy cash flows.

You’d be walking away with cash flows as of day 1 and would secure a higher total return down the line, assuming you’re holding for 3 years at least.

The only wrench here is that typically, securing funds through a loan can take several weeks, sometimes months, especially for first-time buyers.

In the US, buyers who have exhausted all financing avenues can benefit from SBA loans, but anybody outside of America’s going to have to hustle to secure those funds in time to win the transaction.

I’ve lost count of the deals that fell through due to slow lenders or lengthy due diligence requirements. An all-cash offer would pop in and take the deal with it.

There’s a huge opportunity in the space for a lender to change the game and help micro-angels move faster.

In fact, Andrew from MicroAcquire recently raised $50k in non-dilutive capital from Founderpath in like, 3 minutes.

I have no idea what the terms are but that’s fucking amazing. 😂

The entire landscape is changing and new paths are opening for founders (pun intended).

Perhaps a similar revolution is on the way for micro-angels. Only time will tell.

Back to our imaginary deal:

What if you didn’t even have $100k?

What if you went lower, at say $50k cash, or even just $25k cash?

What then?

Scenario C — $50k cash, $50k balance, $48.5k loan

You probably already know the math is going to get pretty janky for a cash flow investor, but it’s worth exploring anyways.

If you were to move forward, your 3-year cash-on-cash returns would look something like this:

Year 1: -7% cash-on-cash, 32% total return

Year 2: 90% cash-on-cash, 162% total return

Year 3: 112% cash-on-cash, 306% total return

For the more risk tolerant micro-angel, this scenario offers an unorthodox path to producing outsized returns, from a cash-on-cash perspective but also in total.

It’s a much more chaotic picture, as you’d sign up to lose money for the first year. Your paper total return would be 32% at the end of the first year because of the valuation increase, but you’d still be bleeding money.

Then, on the second year, your $50k investment basically comes right back. A 90% cash-on-cash return is unheard of and in this case, if it’s something you’re able to sustain and make happen, becomes an asset you start to consider for buy-and-hold.

The 7-year picture on such a project becomes very interesting as the total IRR starts entering micro-angel return ranges that is totally next-level (10x+).

You’d imagine most micro-angels won’t wait 7 years before liquidating. I’d say buy-and-hold is stuff you expect to sell in 7 years. Then by the time you accept it, you’re looking at 10x on your initial investment.

Some obvious advantage in this case:

you can wiggle your way to extreme cash-on-cash returns 12 months post-acquisition,

you can reliably return 3x on your investment by the end of the third year, and

you acquire the option to buy-and-hold or exit anytime thereafter for outsized gains. It’s a micro-option!

Of course, as long as you defer the decision to exit and hold the product, you’d be reaping incredible cash-on-cash returns.

It begs the question: does a rolling fund strategy make sense? Does it make sense to hold a percentage of the portfolio with extreme set ups like this one?

As you build your portfolio, your reliance on the cash flows of each subsequent deal decreases. This means you could start off with more cash in your deals and progressively wean off your own capital as the cashflows of the portfolio grow beyond your needs.

There is an infinite number of possibilities when it comes to cash vs. debt. A big part of that decision is your investing style and personal circumstance.

I’m investing to buy-back my time today rather than bootstrapping up to that. It’s an investment I’m comfortable with despite the lower returns I get from pulling out all my profits.

It helps me reach my goals, and in the grand scheme of things, that’s the entire point of playing this game.

As my portfolio grows, my investment thesis will evolve and I’ll take on more long-term deals that favour higher returns.

How will you decide to play the game?

A micro-angel who isn’t living off of their portfolio’s cashflows to do other projects could feasibly spend all of their time improving the product, which would further push up the IRR. For Micro Angel Fund 1, the goal is to secure low-maintenance cash flows to support ongoing entrepreneurship (partnercrm.co & sellwithbatch.com).

“I’ll pay you X% of the transaction over Y months at a Z% interest rate”

But be careful — you’re playing with a smaller total profit, even though the rate of return is technically higher. That could be a factor if you need to meet personal income targets from your portfolio.