The math behind Micro-SaaS exits & guaranteed micro-angel returns

How to arbitrage micro-acquisition valuations for instant ROI

New technologies create new models create new channels create new products.

The world is constantly redefined, and the rules leveraged for innovation along with it.

For several years, I’ve noticed an emerging pattern in the indie hacker space. Individuals with incredible talent taking their destiny into their own hands, often times to great effect.

There is a great amount of survivorship bias though.

Most people usually tweet and write about their successes, and that produces a warped reality to anyone deciding whether they want in.

The pattern describes a movement of talented full stack individuals who create side projects that take on a life of their own, [hopefully] liberating their creators to commit to full time indie hacking.

What comes after freedom?

Ultimately, these journeys typically end with a liquidation event for the indie hacker that provides a lump sum that justifies giving up the MRR they’ve worked so hard to built up.

While the vast majority of indie hackers set out to liberate themselves, not all pursue the ambition to build a big business, and fewer still have the skills and discipline to build repeatable growth systems that scale the project beyond a single individual.

Typically, weekend warriors hack together a project with the dream to dedicate their full-time to it. Little do most indie hackers realize, that moment of freedom is more fleeting than you think.

Let me explain:

When you get started, the only thing that matters is the main milestone by which you’ll benchmark your ability to be free.

For most, that is a revenue benchmark.

Some peg it at $2k MRR, some at $5k, some at $10k, and so on.

Bootstrapping teams might require even larger break-even points, but the main theme is that the beginning of the journey is defined by setting your sights on the main, primary milestone you identify to enable your future: revenue break-even.

Here’s where it gets tricky:

The vast majority of indie hackers fail spectacularly to reach their goals.

Most end up taking up a new job, joining another startup, or simply sunsetting/selling the project and starting a new one.

Pro tip: If you’re on the indie hacking path, failure is the path. Don’t expect your first project to be the one. Every project leads to the next. It’s a natural flow, and you have to earn your stripes over time. Show up every day, be consistent, and the Pareto principle will carry you to an inevitable win.

As it turns out, building side projects in public is the best way to get hired, because it represents a fundamental truth about how you execute and your ability to materialize progress over time.

Others who do manage to attain their MRR goals are faced with a very ambiguous, very different context birthed by the very freedom they’ve worked so hard to create.

Consider someone who’s managed to reach a $10k MRR milestone for their project all on their own.

Super legit.

The volume of support tickets, feature requests, dev ops and everything in between starts to grow to the point where it feels like a job.

It becomes untenable. Maybe even boring?

The indie hacker is faced with the choice to make a first hire, or assume any additional workload induced by the project, including growing stress created when things go wrong.

That, of course, would presume they’re sticking to their project.

The bigger you are, the more painful every failure can be.

At some size, failure becomes potentially catastrophic considering the level of work implied in fixing critical issues that affect hundreds or thousands of customers. Especially alone.

This is why there are many projects being sold with either very low revenue or very high revenue.

Small & Large, No Medium

You’ll rarely find anything in between, and when you do, the motivation to sell is very low because the project is no longer small, and could be big.

On one hand, one segment has failed to create continuous momentum, and on the other, another has managed to produce great results and is searching for an equally great outcome.

In the middle though, you’ll find people who aren’t quite sure they want to sell, on the simple basis that their product is growing.

Someone with really low revenue might want to sell to exit out of the failed project.

A buyer of such a project would benefit from a potentially great product that has not had enough marketing to ever have a chance at market/product fit.

Someone with high revenue might have worked on the project for some time, recognizes the value in the MRR they’ve managed to build up on their own, and may be uninterested in further operating the project, the responsibility burden of which may be growing.

There are plenty of opportunities in between. That is, projects that have managed to reach market/product fit but which do not yet produce considerable MRR.

Unfortunately, these seldom represent a good acquisition opportunity. Like, put yourself in the shoes of the owner of a project whose MRR is growing at 15% per month steadily.

By the time you’re past your initial benchmark, you may not have thought about what comes next and it can be confusing—even bewildering, to choose which side of the fork to walk on.

This person might decide to list their product on MicroAcquire to gauge the market reaction and what type of valuation they might be able to pull were they to sell today.

However, regardless of the offer they’ll receive, their intention isn’t to sell because they are confident the revenues will continue to grow at the same pace, which would spell a stronger valuation down the line, say, 6-12 months later.

Little do they know that the very fabric of the business is in jeopardy the longer they hold on to their solo reigns.

Things get closer to imploding the deeper down the ocean you go, and a submarine made for one simply can’t go beyond certain depths.

It is way easier to sell a growing, solo product that has very little costs than a bigger, potentially still growing but less profitable product.

What seems like an optimization often leads to needless sacrifice.

This middle segment is interested but not motivated, and that motivation is shrouded by greed, which prescribes that holding their project for longer will result in a more favourable outcome.

Of course, there’s more to motivation than the growth of a product.

Some might consider selling on the simple basis of the absolute dollar amount they’d be accepting, which might be life changing in of itself. You can sell a $25K MRR business for $1M. Sometimes.

But by and large, I’ve noticed that founders of growing products in this mid-section tend to be fishing for information. It sucks.

Interviewing opportunities and taking the time to understand their motivations to start the company, their vision, where they are, and everything in between, is the only way to get an accurate, truthful picture of how likely one might be to transact with you.

Because different motivations create different reasons to sell at different times in the lifecycle, you’ll find different kinds opportunities on various channels.

It’s like chasing after Pokemon. You have to walk across the land, search far and wide!

Channel arbitrage

MicroAcquire and other marketplaces like SwiftExits, Transferslot, IndieMaker, Flippa and so on makes it incredibly easy to expose yourself to seriously good lead flow.

Reaching out manually is mission-critical, too. You don’t have to be super official about it either, just rifle off friendly emails whenever you find something interesting.

There are also dedicated brokerages that have built a reputation on the basis of their ability to attract great deals by precompiling in-depth information and interviews for buyers.

I recently announced the acquisition of Reconcile.ly on Twitter, and FE International CEO Thomas Smale made a really insightful remark that recently came top of mind again:

To which I responded:

Lately, I’ve explored the possible arbitrage created by the existence of different marketplaces and how a savvy, scrappy micro-angel could create instant ROI by redirecting micro-acquisitions to larger buyers.

First, some back-story on why I started thinking about this.

Backstory

In Q1 2018, I nearly bought Shopstorm, a growing portfolio of Shopify apps producing $35k MRR (back then) and throwing off amazing profit margins.

It was a $1.2m deal, and I was financing most of it.

This was a deal I’d had the chance to review as it had been listed on FE International. Their team provide a fantastic prospectus on every listed opportunity.

The MRR produced by the 4-5 apps followed the typical Pareto distribution, with one being responsible for the lion’s share of the revenues.

Despite this, the rolled-up portfolio’s products all benefited from a 2.85x multiple which I had found to be a little aggressive, considering 4 out of the 5 apps were literal duds.

What’s interesting to note here is that this is probably the first time my eyes really opened up to the possibility of a Shopify app roll-up, and the fact I was competing with several buyers indicated some demand on the marketplace that I could serve.

Eventually, the deal fell through because my lender couldn’t qualify the earnings from Shopify payouts alone, and a Quality of Earnings Report was totally out of the question for the sellers.

Because I was financing nearly 70% of the purchase, the lender I worked with needed to go through a level of financial due diligence that was completely incompatible with a small Shopify app portfolio.

Revenues for apps of this kind typically are paid out via PayPal, which can be instantly verifiable. Existing MRR can be accurately quantified by multiplying the number of customers by the pricing tiers to which they belong.

A quality of earnings is a super beefy, multi-page document that seeks to create confidence in a party that the numbers provided on the balance sheet represent an accurate picture of what the new buyer would be dealing with, thereby discounting any irrelevant stuff that only applied to the previous seller.

This is work typically produced by a CPA, but the buyer didn’t have any appetite to pay a five-figure sum to produce a document other buyers weren’t bothering them to acquire.

Eventually, if my memory serves me right, an all-cash offer was offered to the seller and the deal broke down on my side.

The deal died because of paper pushing and speed (+ lack thereof).

At that time, I realized the appetite of SaaS buyers at the PE firm level. I’m talking beyond micro-angel and wealthy angel.

These are dedicated funds that eat up profitable businesses for stable MRR, and they happily bid over each other and pay premium multiples for strong businesses.

It’s the REIT equivalent of the micro-SaaS and SaaS world.

Thomas’ comment is prescient, listing the Reconcile.ly app on FE International today would likely be done at a much higher multiple than my purchase considering, among other things, they are a commission brokerage & the best in their category, in my opinion.

This is why a lightbulb went off in my head when Andrew Gazdecki launched Microacquire. He completely shuffled the cards, and in doing so, opened the portal to a totally new dimension.

I instantly recognized an arbitrage window opening because of my expectation that closing prices for products on MicroAcquire would ultimately be lower than those on FEI, if only due to commission.

Secondly, individuals represent themselves myopically due to the limits of a single person’s experience and perspective, and that’s a double-edged sword that can cost thousands of dollars come time to exit.

There’s going to be a disadvantage compared to a firm whose built an amazing reputation representing high value opportunities to a group of investors they’ve attracted and come to understand.

But that’s barely a rule of thumb. If even that.

Yet the micro-seller might not cover all their bases and miss opportunities for pulling out more value out of their product.

The 4-cap buyer archetype

In real estate, there are certain types of investors who will happily pay a premium (that other investors will balk at) for properties that have very low risk and a very good track record for filling vacancy at or above market rates, in good neighbourhoods.

Reconcile.ly produces ~$58K SDE in profit and it growing on autopilot. I’ve seen products exactly like this one go for 5x-6x — and fast, via such buyers.

That means there’s a strong chance I could offload it right now for $250k+ or higher.

Because I was able to acquire the business at a lower multiple ($150k), a $100k arbitrage was created. An unrealized paper-gain.

The existence of both marketplaces, with each having a unique value proposition for completely different audiences, seeking different types and sizes of transactions, creates that arbitrage.

A savvy micro-angel could acquire something on MicroAcquire, grow it to an ARR level that is interesting to the typical FEI buyer, and then successfully execute a transaction at a high multiple to the highest bidder in between.

FFT: There’s no evidence indicating that FEI buyers aren’t also MicroAcquire buyers, in fact, I’d be willing to bet that the percentage of FEI buyers who also shop on MicroAcquire will steadily grow over time.

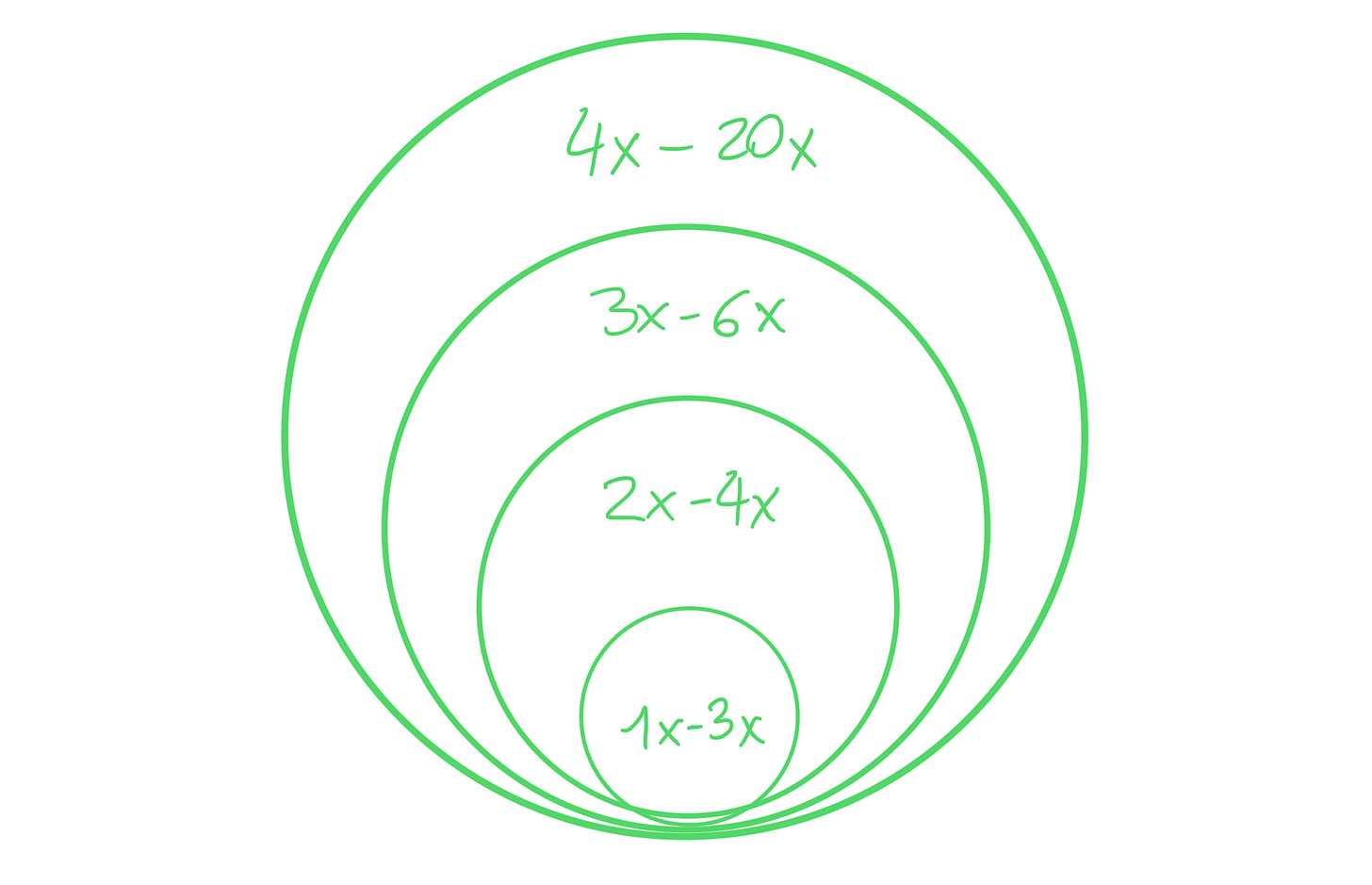

In essence, what I’m describing is the potential interplay between the various sized SaaS acquisition channels, from manual outreach to marketplaces to brokerages to strategic investors and funds.

In a way, this simple truth affords me paper equity gains in excess of $100k for Reconcile.ly as of Day 1 because I closed an excellent deal at excellent terms due to a buyer motivated by an all-cash offer.

This could have an impact on how you source your deals or orchestrate the transactions.

Fatten up your fish so whales take notice

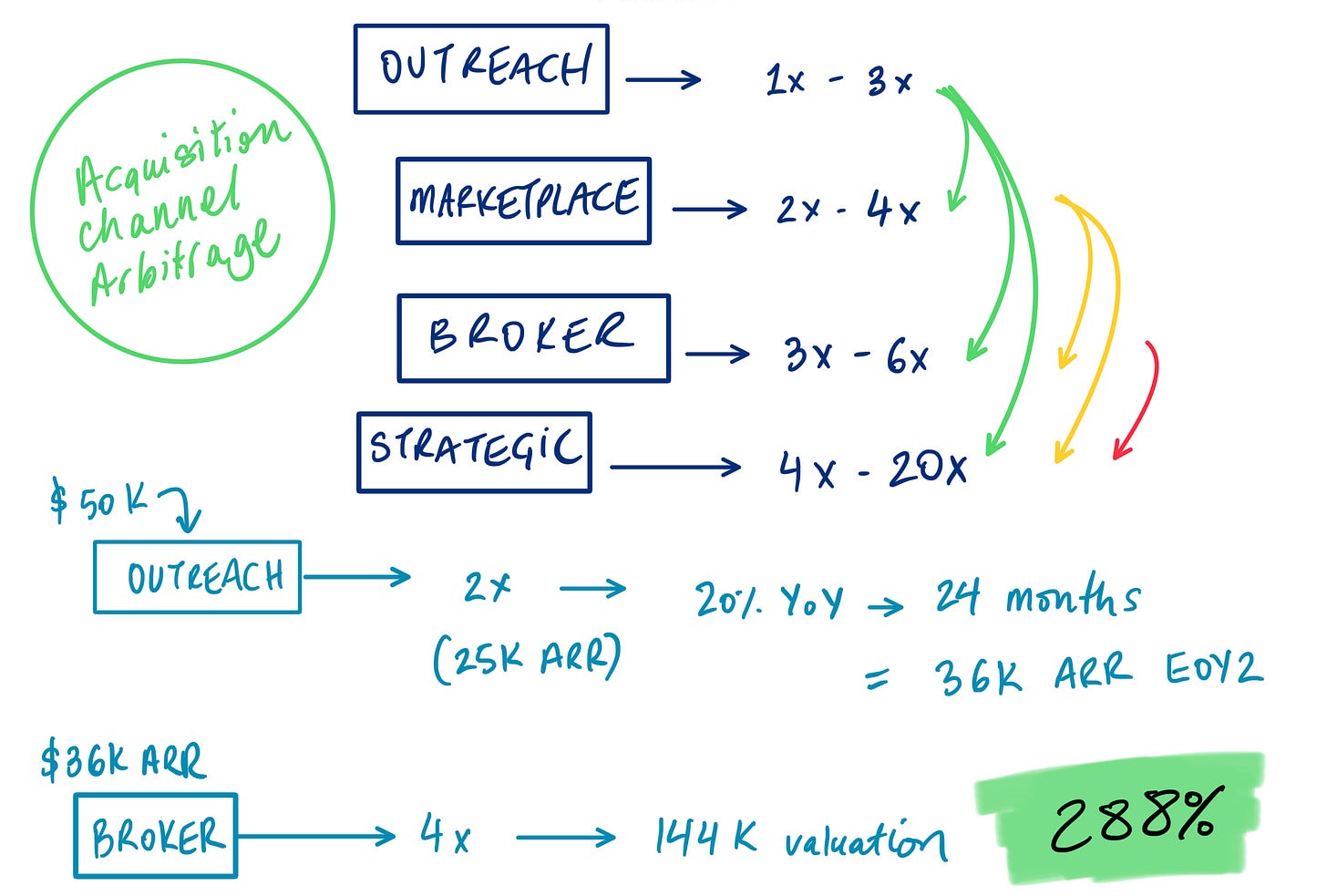

Imagine you’re a micro-angel with $50k to spend.

Every channel has its affinity:

Manual outreach can help you find hidden gems that aren’t on anyone’s radar. It lets you take your time to really get to know the individual, who in some cases, may be willing to accept a lower multiple based on the up-front consideration

I’ve noticed most of my accepted LOIs from manual outreach tend to be in the 1x to 3x range. This is critically important.

Marketplaces are the true game changer by their ability to democratize the process of figuring out what your product is worth (for sellers) while creating a buffet of high-value opportunities that are ready & open to sell.

The vast majority of my accepted LOIs in this segment contained an offer at a 2x to 4x multiple. Already higher than outreach!

Brokerages create a unique, curated environment wherewith every listing tends to create a feeding frenzy among a population of thousands upon thousands of buyers with strong buying power.

As I learned years ago, brokerage-focused buyers mean business and put forward ultra-aggressive offers in the 3x-6x range, often all-cash and with no real strings attached.

Strategic buyers are the rarest, but also the most valuable, as the product’s IP contains a unique advantage to the buyer that they are prepared to field a massive premium for.

Offers will range wildly (upwards) from 4x to 20x ARR.

Because each channel’s typical buyer is a very defined persona, each with their own unique buying power and style, the typical offer range for the same product will vary wildly based on upon which segment the buyer belongs to.

Considering the typical multiples on each channel, that $50k will go so far depending on the kind of channel you source from:

While doing outreach, you come across an opportunity and get in touch directly with the owner of a product.

You receive a reply indicating some interest, and eventually manage to acquire the product at a 2x ARR multiple.

That assumes your $50k buys you $25k ARR.

If you were to follow the Fund 1 model, which seeks to perceive cash-on-cash returns during a period of 24 months while the (default-alive) product grows, you’d end up holding this $50k investment for at least 2 years.

In that time, imagine you perceived year-on-year ARR growth of 20%, leading you to the following 2 year performance:

Start of Year 1: $25k ARR

End of Year 1: $30k ARR (+20%)

End of Year 2: $36k ARR (+20%)

You’d end up with a $36K ARR product, the size of which is now interesting to buyers across both marketplaces and brokerages.

Assuming you were to list these products at typical ranges for these channels, you’d open yourself to an interesting opportunity:

Marketplace: 2x to 4x → $72k to $144k (44%-188% return range)

Brokerage: 3x to 6x → $108k to $216k (116%-332% return range)

All in, the fact you’d have acquired the product at a low multiple through your outreach efforts grants you the ability to reap higher multiples for the same ARR you purchased, while gleaning additional bonuses for any ARR growth you would have benefited from during your holding period.

This is really unbaked, and I’d need to do many more deals to qualify whether this persists beyond my own operations.

But I have a strong hunch that there are guaranteed paper returns made possible by the existence of this natural segmentation.

There’s a spectrum of sellers, too. So far, I’ve noticed two kinds of sellers, which sort of covers the spectrum of risk in this case:

Sellers who are happily willing to give up a higher selling price in order to secure an all-cash, no strings attached transaction they can immediately exit through

Sellers who are willing to give up a piece of the up-front consideration for a larger total amount, which makes cash-balances more available as financing tools for the buyer

I’m a little bothered by something in this model. I don’t want to get into the business of meaningless arbitrage, though something tells me this is more of a moral compass thing than anything else.

There’s nothing explicitly wrong with it — the laws of supply & demand are still respected. What feels implicitly dirty as a creator is the idea of immediately reselling something I buy.

But… buying something at a lower-than-usual multiple which is default-alive and which could reasonably be resold later on via an acquisition channel most likely to produce an outsized return makes sense to me every time I revisit the idea.

The goal is to buy a product that is teetering on the edge of a given segment size. Big, round numbers. $50k, $100k, $250k, etc.

You want excellent products that need help, direct-purchase them at fair multiples considering their stages, grow their ARR to the threshold that gets larger investors interested (in the next channel), and sell to the most motivated buyer in that new range.

This logic likely also applies on a geographical scale as well.

There are so many awesomely talented people scattered throughout the world that are producing or have produced software products that fit the bill.

They don’t necessarily have access to the knowledge or tools to make the most out of their product. Community is opportunity.

There’s all sorts of combinations, and it is expected that an investor that takes their time will eventually find something to acquire at favourable terms, which opens up the possibility of guaranteed returns if sold to a buyer in the next segment.

It’s another great illustration of bootstrapping 2.0, and how each party plays a specific role in the value chain, and how each role creates value in a unique way for all parties involved in a way that perpetuates a big, virtuous cycle.

2x on Reconcile.ly in <90 days?

Over the month of March, things were rough for Reconcile.ly.

I fielded some immediate improvements, but could not leverage the same levers that the growth of the product had so far been predicated upon. And revenue growth was flat.

Ad costs were extremely variable and not at all profitable, and the initial support burden created by tax season gave me whiplash as I wondered if things would stay that complicated and busy for long.

While it wasn’t part of the plan, I eventually asked myself what I might do in the eventuality that I lost confidence I could grow the product on my own.

Since I haven’t yet even tried doing that, it’s too early to throw in that towel, but it’d be nice to know there’s an escape pod ready in the case my ship starts to disintegrate and I need safe re-entry into the atmosphere.

Incidentally, that might provide some real experience relative to my arbitrage hypothesis.

Reconcilely very much teeters on the both edges of the $50K ARR threshold, which attracts buyers on both marketplaces and brokerages.

I asked myself what might happen if I listed Reconcilely for sale right now. Especially in the context of testing how immediate the liquidity of the portfolio really is.

Provided the need to rapidly exit the businesses without destroying my returns, could I reduce the risk involved in quickly liquidating my position or better yet, being able to reverse an acquisition provided its fundamentals fail to follow through post-purchase?

That might be an extreme case, since I don’t regret purchasing Reconcilely at all — quite the opposite.

That said, would I part with it 60-90 days into ownership provided I could return 2x immediately?

Probably. Not doing so would probably be dumb/irresponsible considering the model of the fund.

I could double-up that capital and go buy double the revenue today, potentially quadrupling up on my initial spend and thus my total return. I like that.

Or I could re-field my initial spend and then pocket the other half as a cash-on-cash return for the fund, reducing the MRR growth burden considerably.

I’m likely going to test that hypothesis and see what Reconcile.ly might fetch in the next 30 days. Maybe throughout May. The point would be to test offers across marketplaces as well as brokerages.

Especially considering I’ve been thinking long and hard about raising outside funds for Batch but failing to justify doing so provided readily available funds through MicroAngel I and/or its proceeds.

It would sure be nice to sell Reconcilely for $300k+, buy another $150k property to re-secure my $5k MRR, and funnel the remaining $150k proceeds into Batch as a pre-seed, without touching my funds.

Importantly, the folks at FEI would likely do a much better job of packaging the opportunity for their vast network of buyers than I ever would on my own.

If the listing lands in the inboxes of the same buyers I lost so many deals to in the past, I’m confident I could likely pull close to the ask.

If and when this arbitrage experiment takes place, I’ll be sure to compare it to the idea of operating and/or holding.

One might re-list say, 90 days after buying on the assumption that core changes have been made soon after the initial acquisition, justifying a greater multiple despite the short amount of time.

That would be an even more deliberate approach that, when hybridized to the dynamics of different marketplaces and geographies, can turn this game into the likes of 4D chess.

Instead of a model where I’d be buying many products during a defined period, and then sequentially working on the portfolio’s products, I’d instead buy and immediately implement fixes so I can list my first purchase for sale during the ~90 days it would take to find and close my second acquisition.

Unfortunately, I’ve yet to close a second deal since March, which means I’ve spent 56 days prospecting.

In that time, Reconcilely has grown, further increasing possible gains. It would be really interesting to consider a piece of the fund as ‘rapid fixes’ and others as ‘fix and hold’.

That might make it possible to guarantee cash-on-cash returns without ever exposing myself to the risk of failing to secure MRR growth for portfolio assets.

As everything, time will hopefully tell.

What would you do in my shoes?

Good read? Share it with a friend!1

Thanks to the following Newsletter Sponsors for their support:

MicroAcquire, Arni Westh, John Speed & the many other silent sponsors

LOVE how you layout micro acquisition in such an elegant way!1